Eva Barois de Caevel’s curatorial work addresses more than art. It brings our attention both to words’ limitations and to their limiting power, as it asks us to think deeply about how we use words to describe-and understand-what we see before us. It also compels us to consider art broadly, in terms of the discourses-political, racial, gendered, art historical- in which it circulates. Her curatorial practice uses traditional methods and approaches, even as it investigates new ways to critique these discourses. By bringing our attention to a great range of representations, which speak across identity boundaries (i.e. race, class, gender, sexuality, age, profession), she suggests new, empowering discourses, within which we can build a claim for the visibility of artists from a variety of cultural spaces, and suggest art’s potential to transform individuals into powerful, visible subjects.

Barois de Caevel begins with work that says something, that engages with issues of race, gender, immigration, globalization. But she does not tell us what it says. She is keenly aware that curation can be misleading, especially if it uses words that have their origins in other cultural systems. Take, for example, her work with queer artists from Africa: In refusing to use the terms heterosexuality or homosexuality, she draws our attention to the socio-political limitations of these terms, and creates a space in which the works can teach us something about the human experience that we might not have considered before.

This approach been called « unflinching, » (1) but we might also call it « clear eyed, » for Barois de Caevel brings the Western gaze-and its attendant vocabulary-into visibility. She curates art that is incongruent with this gaze, and without apology or interpretation, she allows the art to resist its omissions and categorizations. She bring us to see, in other words, the many cracks which are often rendered invisible by the restricting vision of the gaze itself. She forces us to find new ways to see, and new ways to articulate what we see.

Consider the difficulty of this approach: On one hand, when art from other cultural spaces is exhibited in the West, Barois de Caevel must resist the impulses that would render it exoticized, foreignize, othered. And yet, she must also resist a domesticating impulse, which would seamlessly situate the objects with discourses that they are actively trying to resist, speaking of them in terms constructed in West.

Barois de Caevel challenges us to see more than the art itself. She challenges us to see how we see. This is a critical intervention in the art world of this 21st century. It is also fundamental to how we see, and understand, the world around us. It challenges us to experience art in the sense of Fanon’s words in his seminal text, Black Skin, White Masks: « My final prayer: O my body, make of me always a man who questions! »

Frieda Ekotto. How would you describe your reactions to receiving the ICI’s 2014 Independent Vision Curatorial Award?

Eva Barois de Caevel: My first reaction was an immense surprise, and also, of course, great joy. It was an immense surprise because, to be honest, I feel my practice is still very young, experimental and political, and is quite demanding, and I know from experience that it can deter viewers. I was afraid that it would not be understood, especially when communicated via the normalizing, necessary but always frustrating, structures of a numbered file. In regards to my work, I often have had the feeling of being in the zone of complete experimentation, and also rather solitary. My professional practice as curator is done with as much seriousness as possible, and in following my deepest convictions, but without the expectation that I will be able to obtain my objectives, or that I won’t be completely wrong. This doubt is healthy and helpful, but the recognition of ICI’s 2014 Independent Vision Curatorial Award gives me the possibility to mark a stopping point, a moment in this progression in which I can examine the work I’ve done, and admit-with joy-that it touches and interests individuals around the world, notably other professionals in contemporary art. It gives me the courage, and the energy, to continue my work with increased confidence.

Nancy Spector, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, has recently declared that your « unflinching curatorial practice tackles some of today’s most urgent issues, including sexuality and human rights, in a postcolonial world« . In your opinion, which of your most recent initiatives testifies the most to this « unflinching » character of your curatorial practice, and why?

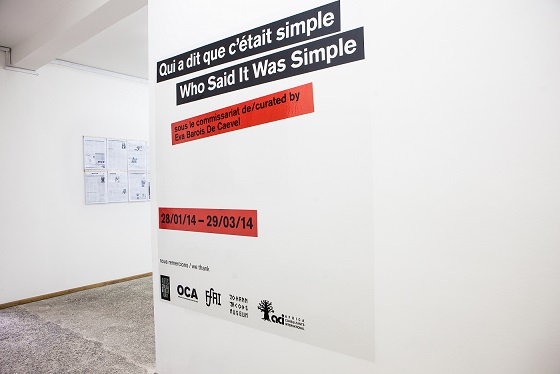

The material I have been working with (a publication is forthcoming) at Raw Material Company since last January is without a double most emblematic of this aspect of my practice. Incidentally, one of the requirements of the materials judged by Nancy Spector was that it be presented in detail. I chose to focus upon « Who Said It Was Simple, » the exhibition I proposed to Raw. « Who Said It Was Easy » is a project that challenges us at several levels: thematically, theoretically and formally. It is also challenging by the fact that it has refused to conform, from its conception, to Western discourses, which are essentially forms of evangelizing to Africans via a moral aesthetic.

Most of my interlocutors, before seeing the exhibition, were expecting-were hoping-to help with a sort of naïve preaching, via works of contemporary art, of Western values in the defense of homosexuality. Some Western expatriates and neo-missionaries were, actually, quite upset that the exhibition wasn’t in step with « Gay Pride. »

Yet as we were presenting to the Senegalese public contemporary art that engaged with ideas about contemporary sexuality, work produced by African and diasporic artists, and which had already been exhibited in the West and received in a certain fashion, it was essential to me, that they be accompanied by a radically contextualizing theoretical and critical apparatus. In other words, not works in a first phase, not works which, in this context, would have been just as many imports without meaning.

The temporal division of the exhibition into chapters (separating out the mediation and the debate about the materiality of the works) was something with which we were in agreement with Koyo Kouoh (Raw Material Company’s founder and artistic director), and which worked very well.

My exhibition was subsequently conceived of as a research laboratory which, being based upon archives, university research and literature, and in offering multiple occasions for dialogue, asked about the relationship between African and Western cultural institutions, as well as about the stakes of the duality of homosexual/heterosexual as a colonial export, and about my particular position as a curator of a French exposition, who is also of Senegalese origin, but who grew up cut off from all contact with Senegal.

Ms. Spector has also indicated that you are receiving this prestigious award because by « working collaboratively to encourage dialogue and participation among your audiences, with issues both local and global, [you are]courageously expanding the curatorial field« . Are there other ways in which you consider that aspects of your practice have contributed to expand the curatorial field?

It is hard to respond to this question, as my practice is still young. That being said, I hope, and time will tell, that the work I am doing, as it regards the scope of a curatorial practice, will indeed grow in diverse ways. A first aspect of this would be the material form given to an exhibition. I try-and this something that I would like to push even further-not to restrain myself to selecting and presenting work, but also as to act as an editor of the accompanying and mediating texts. I would like to find other ways of conveying context in a critical apparatus that breaks with traditional exhibition forms. Not for its own say, but because this seems, to me, to be essential. I am, for example, currently writing a project for which either I, or someone for me, will create objects, which will seem strange within an exhibition, but which, it seems to me, are necessary to include as critically active material.

Another point is related to the balancing of the material hegemony of exhibition techniques, and more generally, techniques related to the field of research that are used in curating. Let me explain: When you think of an exhibition, or, for example, archival work, you are almost always using Western-centered methodologies. This is not a problem in and of itself, but if your analysis does not start there when you exhibit or write about works of art that are produced by, or related to, non-Western cultures, it is a problem. It is important that the curator reflect on specific or mixed forms. This happens where there is knowledge of the cultural history of non-Western cultures and an analysis of the relationships they have, today, with globalization in the cultural field.

A last element, more or less of the same sort, concerns the language and vocabulary by which we judge phenomena that occur via works of art. I think my work on the term « homosexuality » for « Who Said It Was Simple » is an eloquent example. These are a few of examples of the landscape over which it would serve curators well to travel, and over which I plan to work in the years to come.

Finally, I would add that, in a general sense, it is healthy for curators to not limit themselves solely to formal issues, or issues internal to the history of art. Artists themselves work in landscapes as diverse as anthropology and sociology, and create works that necessitate new support and specific ways of being presented.

A graduate of the Université de Paris-Sorbonne Paris IV in Contemporary Art History in 2011 and in Curatorial Training in 2012, your research as a student has been primarily concerned with the moving image, the evolution of experimental cinema, the history of production structures and the artistic entities behind them, and issues of intermediality. To what extent has your academic training influenced your work as a curator? To what extent has it prepared you to examine postcolonial questions and socially engaged practices in contemporary art?

I was very grateful for my education at the Sorbonne, which gave me a historical and theoretical background. I needed this training to be well grounded conceptually, but it was absolutely not in this context that I was able to develop my interest in postcolonial questions and my practice of social engagement. The Sorbonne’s training in the history of contemporary art is excellent, but it is still based on Western art history and on the major artistic movements of the 20th and 21st centuries. It doesn’t allow much time for incursions into areas less explored in France. In the end, my knowledge about the questions that are now central to my work has been more or less self-taught. It was born and nourished by my own research, by discussions with figures in the contemporary art world, whom I had the opportunity to meet outside the university sector, as well as through professional experiences and my travels.

Many of your recent curatorial projects have addressed issues of race, sexualities, human rights, globalization, postcolonial legacies and alterity, images of the self, and the epistemological violence caused by Western-centric labels. Who are some of the thinkers and artists that have contributed (positively or less positively) to the vast and profound critical reflections you bring to these projects?

This is also a huge question. To begin, I should make something clear: I grew up in a Western family, white, educated. They gave me access to books, none of which were by African thinkers. A family that we would not be able to call racist, but which was racist in the sense that we know it to be in France, that is to say, living in great ignorance of other cultures with which they share a history and a present, but, especially, in total ignorance of this ignorance. I began reading as a tentative response to this deficit. I read Fanon, Césaire, Senghor, the first works that I could get my hands on. Later I went to the library at the Musée du quai Branly diligently, searching for stories about African kings and queens, and also for details about colonial history. It was at also at this time that I read Cheikh Anta Diop, and for the first time, works that put questions of contemporary art and postcolonialism into perspective though both specific and popular prisms, for example, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity by Monica L. Miller.

Today, many theoretical and critical works inspire me, for example texts by Paul Gilroy, Édouard Glissant or Thomas McEvilley, as well as works of literature. I particularly like Michel Leiris, J. M. G. Le Clézio, Ken Bugul . I also love Victor Segalen enormously; Essay on Exoticism has been an important source of reflection. Reading is essential to my process of conceiving of an exhibition. For « Who Said It Was Simple, » I made the choice to reveal my bibliography. Most importantly, we found texts by Carlos Motta, Cheikh Ibrahima Niang, Joseph Massad, Ifi Amadiume, Éric Fassin, Samar Habib, Stephen O. Murray et Will Roscoe, Stella Magliani-Belkacem and Félix Boggio Ewanjié-Épée, as well as articles from the magazine Feminist Africa Journal. Of course, artists are a first source of inspiration, and I also love to read their work and listen to them speak. I could cite many, but Yinka Shonibaré Mbe or Kader Attia are two artists who inspire me, and whose ideas inspire me. Currently I’m also interested in Fred Wilson and Chris Ofili.

Good exhibition catalogues are also always valuable tools. And of course I follow-via their both their written work and presentations-the doings of curators whom I admire: Simon Njami, Christine Eyene, Okwui Enwezor, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Koyo Kouoh and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. To answer your question completely, it is equally true that artistic practices which I don’t like as well-or not at all-just like artistic discourses with which I don’t agree are also, in their own way, a source of inspiration, or of redaction. I think that you know, for example, my critical work on Zanele Muholi, or on the presence and the treatment of the veil in contemporary African and African diasporic art.

You are based in Paris, but you have also lived in Morocco, Madagascar, and especially in Dakar, Senegal, where you have completed a curatorial residency at Raw Material Company – centre for art, knowledge and society. Before and during your experiences in Africa, you have studied African art exhibition structures and the modes of collaboration and relation between Western structures and African ones, and more specifically the way otherness is dealt with and the issue of mimicry. What can you say about these structures and the ways in which your awareness of them has influenced your curatorial practice?

What was interesting to me was the presence-very recent-on the international scene of places located in Africa, which in the West we knew about (their existence and their programming) via « international » communications, especially via collaborative networks and financial support linked to the West. The problem is not to be for or against this. I was simply curious to understand how these places functioned, because I was convinced that they should be confronted by the very concrete questions that interested me, for example, the possible revision of curatorial methods that do not exist according to the Western epistemological norms. How could curators work in these exhibition spaces? How did they consider specific contexts even if they had, almost always, learned their trade in the West? It was with these questions that I set about to travel to a few African countries. In Morocco, I was able to observe what was happing in different places (often managed by expatriates). At the Cinémathèque de Tanger, in Madagascar, I worked with a project supported by an artist financed by the Maison Rouge. In Senegal I worked at the Raw Material Company, but also with many other municipal cultural institutions.

The presence of foreign cultural institutions was strong everywhere, notably the Institut Français. My experiences and/or observations all were formative. Most were painfully lacking in a consideration of their relationship with the local and the global, and in critical postcolonial thought. This was even catastrophic at times, and it convinced me of the necessity, at my level, to try to treat these questions and to propose a renovated curatorial practice that could correspond to the specific issues of each place. That is what Koyo proposed, and what we finally worked on together with the Raw team. I am very happy and proud of this project for these reasons. Raw is a very special place, really unique. So many things are possible, and it has been a great opportunity for me to be part of this collaboration. From there I was able to send my questions by mail to places that I had identified in a number of African countries, from Egypt to South Africa. Otherwise, each time I have the opportunity to meet figures in the contemporary African art world, who have worked in Africa, I continue my inquiry. It’s a work in progress that had its origin in a thesis project that I have decided, for the time being, to carry out alone because it was not met with enthusiasm in France, and which I hope to see succeed in one form or another soon.

In your practice, you have considered the necessity of specific curatorial presentations that challenge the Western patterns on which the design and making of exhibitions are globally based. How does this translate at the level of the concrete curatorial choices you have had to make recently? Can you give me a few examples?

I am going to give two specific examples. The first has to with the way the materials are offered to the pubic (in time and space, materially, and in terms of discourse). The second involves the physical presence of the curator as a key to the exhibition as a whole. The first point consists in interrogating oneself about the modalities of reception, and, as was the case, for example, in Dakar, to imagine new ways to adapt ourselves to a reception that is unknown to us based only on what we can perceive. In Senegal I was struck by the performative manner of living the culture and of involving oneself in works of art. I equally admired the art of debate, which occurred after each film screening, talk, or theatrical or dance performance at which I was present. Following this feeling, I tried to experiment, notably by proposing a first chapter of a series without any work: this would create a waiting, a narration, but would also make different critical positions, which were made by different curators, appear about the works.

In addition, my exhibition also included works, but their inclusion was performative: films, and a performance that had not been prearranged, but which Issa Samb suggested after finding out about the exhibition. Moreover, in my opinion, the debates that took place after each session, as well as in the seminars, were in a certain sense a « work, » if we follow an aesthetic proper to practices we call socially engaged. I tried to create the discourse and a context in which the public would be able to, on one hand, chose, imagine, the works that they would have liked to have seen in the exhibition, and on the other hand to have the ability to present their arguments for a next chapter in the series. Furthermore, during these discussions, we sometimes spoke of other works of art, which were not there physically, but which still participated in their own way to the exhibition. The second point is similar: I tried to think about how to present an exhibition differently than through the usual mediating supports. In Dakar, these supports seemed neither sufficient nor appropriate. There were interpretive texts available in French and English, but I was also physically present when the exhibition was open, as well as during its related activities. I had, as I said above, also put my library on display, which I found myself adding to during the course of the exhibition. Many elements of the exposition had to be read through a conversation with me: this was the case for the press archive and the maps, whose reading could take on different meanings.

When speaking with the public, I always brought up my meeting with Professor Niang from the Université Cheikh Anta Diop, and the problems and doubts I faced in creating this exhibition. I made clear my position, nationality and, right away, my history, as it regarded my presence at Raw. I lived at Raw. You might say that it was rather performative, and exhausting, but I think the exchanges were really constructive. So it is this sort of thing. They are attempts to change Western exposition modes, which count on the familiarity of the viewer, on certain behaviours, on reactions to a history that is proper to the West. I don’t know what I will keep or change in the future, following the work I’ve done at Dakar on this, but it certainly is a direction in which I wish to continue.

The theoretical notion of « the archive » and the concrete materiality of archives both seem to play an important role in your curatorial practice (e.g. the exhibition Who Said It Was Simple). Do you believe this to be the result of a particular curatorial stance on your behalf and (if so) what would you say motivates it?

My interest in archives is linked to a conviction that a curator’s work is scientific and that it consists of research and of contextualizing works within art history, as well as, more globally, within the contemporary world. Another element, which is less obvious, is the idea that it can be interesting to show the connections that are subtexts to the exhibition. This is, in any case, something that is important to me personally. For archives, of texts or artefacts, allow this. It can itself be exhibited as an object. It has its own particular position, which, it seems to me, is well suited to being present with the art. I think, then, that my interest in this material comes from my desire, which we’ve already discussed, in finding new means of mediation, and of transmitting knowledge, in the context of an exhibition. Moreover, I am very interested in what comes before an art work in the life of an artist, and, undeniably, archives are a material that are very present in this moment. I also want to interrogate my own archival practice, as far as being a curator. Perhaps to understand the interactions that we can have with this material, what it changes in terms of reading levels for the public. And then, of course, as far as it concerns colonial and postcolonial questions, especially when considered in their popular iterations, which are so interesting to me. Archival material is ideal, perhaps even the best, in making us able to feel historical realities in ways different than discursive texts. And archives are all the more interesting for the fact that they, too, need to be interrogated, because their forms and methodologies, on a global level, fall under a Western epistemology.

In an article you have recently written for the online magazine Afrikadaa: Afro Design and Contemporary Arts, you interrogate the place of the veil in contemporary art, and you write: « It is the reinvestment of men and women who came from non-Western countries in the fields of research, writing, as well as contemporary fine arts that would allow to really decolonise both culture and gender (« et la culture et le genre« ) » (18). Are there examples of such decolonisation already? What role do you think curators can (and maybe should) play in this regard?

Yes, of course there are examples of this decolonizing work, which is reassuring, actually. This was written in the context of a critique of a body of works that I personally judge to be dangerous, because they reproduce imperial thought, in a form through which is circulated in the colonial period but which has been interiorized. All work that succeeds, already, at freeing itself from this, attracts my attention.

Currently, I am giving particular attention to the work of Kader Attia, Adelita Husni-Bey, Mark Boulos, Bouchra Khalili, Kapwani Kiwanga, Jelili Atiku ou Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, but I could cite many other artists. What I find constructive, are the works that admit their existence as living objects in a world globally postcolonial and which produce, themselves, new discourses about this situation.

But I am also grateful when I come into contact with works that liberate themselves from these problems, or which treat them subtly: I loved the exhibition devoted to Chris Ofili at the New Museum. There are these paintings that become more sensual, which mix Western art, questions of race and a fascination for Trinidad. There is also this idea of « camouflage »: black skin/Western distance. It’s beautiful, thrilling, everything but heavy. What role can and should curators play in this decolonization of culture and genre? That of the force of suggestion and of critical insistence.

I think that the best way to play this role is to exist in the first place, as a curator, who is black, a woman, etc. To exist and be recognized. And to propose a way of doing one’s work which corresponds to my reality and which reaches us in history and in the present. To not exist on the margins, but within the world, among others.

In March 2014, in Dakar, you addressed an audience gathered to launch the sixth issue of the online magazine Afrikadaa « Be National ». Your talk was accompanied by a projection of the works of South African artists Zanele Muholi and Nandipha Mntambo. The 2009 exhibition « Innovative Women, » from which these works originated, had caused violent reactions at its opening in Johannesburg. All the while you projected these works, you reminded the audience of the importance of posing the question of words (« poser la question des mots ») such as gender, race, and identity, as you do in your article on the veil in contemporary art. As a curator, do you think it is your mission to pose these questions? How would you qualify artists, like Latifah Echakhhch, whose works, you seem to suggest, instill this kind of interrogation in their audience?

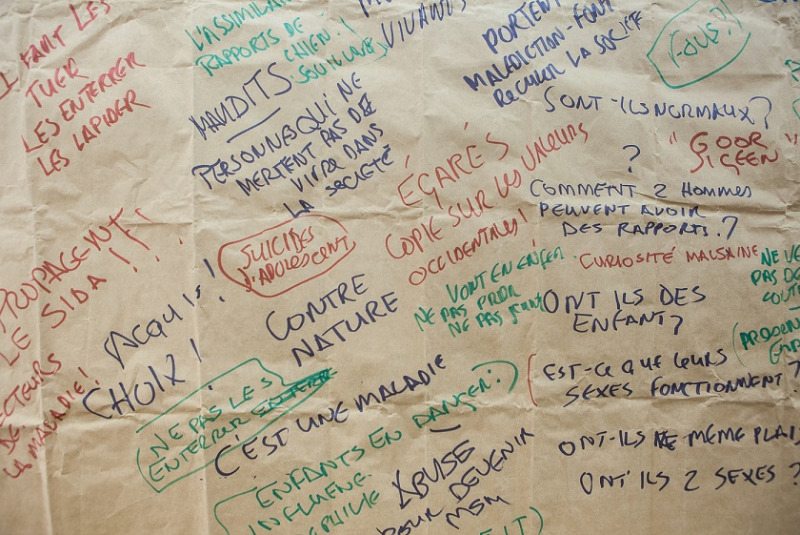

I think that this question of words is essential as soon as we begin to practice an activity in which words are of extreme importance. Yet I am often surprised by the lack of rigor at this level, in contemporary art in general. I don’t know if this really is my mission; I simply have the impression that it is necessary to bring attention to it. What I did at Dakar with the word « homosexuality » was essential. It was the first thing to be done for the public to understand, right away, that what was before them was not what they expected, that they were going to have to make an effort, an effort that started there, in the geographic origin and moral and political worth of words that we use to describe a reality. To make the choice not to use the world « homosexuality » was to postulate a healthy and complete difference of the Other. An idea of Victor Segalen that pleases me immensely. And yes, this was part of my work in so far as I was working in a place and coordinating a program within which we were showing objects by African artists that had to do with sexual practices, works which the Western world has already taken in by qualifying them as « homosexual. »

As it concerns Latifah Echakch, I had referred to her in this article, not exactly to illustrate the idea of importance given to words, but to give an example of a process whose evolution I admired, in terms of the possibility it suggested for liberating oneself from insidious neo-imperialist discourses, and in terms of its resistance to seductive holes into which a « foreign » artist could easily sink. It would require a lengthy explanation, but it is for this that I cited her work at the end of my article. I had, moreover, used as illustration, Echakhch’s work in which we can read, deep in the explanatory notes, « Space to be filled by the foreign, » a phrase which I read to be a sign of taking this into consciousness. Indeed, it is true that I love the idea that words can also be a means of filling the space with the foreign: if we change the words, if we move from « homosexuality » to « goorjigeen » and all the other Woolof words which don’t exactly mean « homosexuality, » what happens?

During the same address (in Dakar, March 2104), you also said: » être gay ou lesbienne [en Afrique]est une structuration nouvelle, héritée d’une vision hétéro-normée et homophobe occidentale, que la modernité et la mondialisation ont diffusé et rendu désirable dans d’autres aires géographiques. Exiger une reconnaissance de ces structures, qui sont bel et bien nouvelles, par le biais, notamment, de l’art contemporain comme le font Muholi et Mntambo est une activité intéressante (puisque un nombre croissant d’individus s’y reconnaissent), mais est une activité qui n’a rien d’a priori » juste » [

] Le vernissage d’ » Innovative Women » et la guerre qui y éclata fut non pas une lutte entre le Bien (les artistes) et le Mal (le ministère) (vision réductrice occidentalo-centrée), mais une lutte entre tradition et modernité, entre intérieur et extérieur. »

As your writings on the veil question make clear, there is a very fine line between trying to address dichotomies in art and art that partakes in and reproduces these same dichotomies. If we transport these reflections to the sphere of sexualities and sexual identities, what would a productive artistic stance towards these dichotomies look like, in your opinion?

The dichotomy you mention is one that exists between artistic and state discourses. What I am attempting to explain, what I propose as a critical response to representations of the veil and of sexuality in contemporary African and diasporic art, is that, even when we say that we are opposed to a national thought deemed archaic, patriotic and anti-liberation, we can still reproduce imperialist discourses, and in this way perpetuate an internal divide in society. One we produce, and which produces imperialist politics and behaviors.

A simple example of this process is the one I suggested in critiquing representations of the veil by women artists in the Maghreb and the Middle East. These representations are directed against specific states and societies, but they are also tantamount to interiorizations of positions of domination. They reactivate the imperialist politics these societies were subjected to (for example the ceremonies of deveiling in colonial Algeria). What does not seem productive in these artistic propositions is the fact that their discourse settles for adapting to the West, without suggesting anything, and without changing anything, within the non-Western societies that they are concerned with (all it produces, ultimately, is division and conflict within these societies).

Yet I think that artists can create objects that remove them from this dichotomy and reposition the debate according to issues proper to their societies; it is here, it seems, that we could see an innovative and productive artistic vision come into existence.

The question of modernity and the webs it casts around the concepts you are interested in teasing out (like here justice, sexualities, sexual identities) seems to be recurrent in your writings and practice. What is modernity for you? In what ways do you think that your conceptualisation and interrogation of modernity influence your curatorial practice?

It’s not a concept that, at the moment, I am trying to conceptualize or interrogate in my practice. In the case of the speech in Dakar you reference, the term « modernity » referred simply to the world after colonization had passed over it, to, in short, to the contemporary world caught in recent history. I was using the term vernacularly, without binding myself to a historical or universal definition.

Interview by Frieda Ekotto

The University of Michigan

(1) Nancy Spector, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.///Article N° : 12711