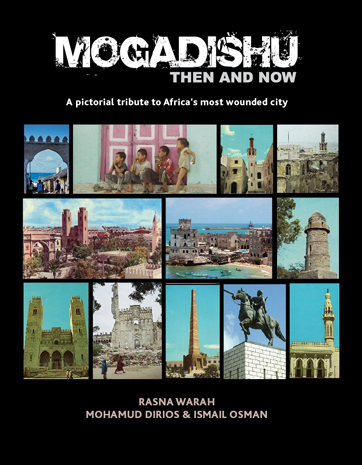

Rasna Warah is a Kenyan journalist, photographer and author (1) who has paid particular attention these past years to the history of Mogadishu, Somalia. This acute interest first brought her to Somalia in November 2011, and eventually led to the publication of Mogadishu Then and Now. A pictorial tribute to Africa’s most wounded city, a book « dedicated to the children and youth of Mogadishu who have never known lasting peace ». The book was published in collaboration with Ismail Osman and Mohamud Dirios, former director of the town’s Somali National Museums. In « an attempt to restore the splendour of Mogadishu in the Somali people’s collective memory (…) », the work presents two intertwined types of images: those captured by Rasna Warah’s own camera, and those patiently collected by the Somali Cultural & Research Center, today based in Ohio, US.

Although the reproduction of the images and the lack of contextualisation of certain historical pictures is at times disappointing, the whole work – « a labour of love », as Warah puts it – brings us to reflect on the ways in which one can broach memory (2) in the digital era and in situations in which archives have materially disappeared subsequent to war, or remain inaccessible, unattainable.

Finally, although taking unbeaten paths, to the extent the author seems open to exploring any track that might enlighten the conflagration of what used to be a cosmopolitan city, (and more generally country), Warah, in the footsteps of political scientists such asAfyare Abdi Elmi, recalls in one of the numerous article in the book that: « (…) any analysis of the collapse of Mogadishu should not be viewed through the prism of clan identity or clan competition, but rather should be seen as a consequence of uneven development that favoured some groups and led to competition for resources among group leaders who mobilised around clan identity to pursue their own individual ambitions. » (3)

For a different point of view, it is also worth noting that an eponymous exhibition was set up thanks to Turkish sponsorships (as was a Turkish edition of the book), reflecting the geopolitical evolutions taking place in this African region that the press portrays in contrasting lights: relative renaissance alongside major security challenges and the urgent need to rebuild the rule of law (4).

In the introduction to the book, you wrote that your arrival in Mogadishu in November 2011 followed an « unplanned (…) foolish (some might say) visit ». The texts published in the book show that you gathered material on the history of Somalia, read, met or interviewed intellectuals and scholars working on it. Can you talk more about your own experience on arrival in Mogadishu? What exactly were you looking for from a photographic point of view? Did perspective shift once you were there?

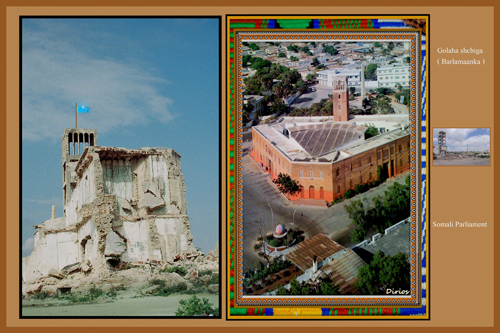

When I decided to go to Mogadishu in November 2011, I didn’t know what to expect. I had only seen images of the city that showed a city at war with itself. It was only when I got there that I realised that the city had a long history and that some of the buildings were centuries old. When I got back, I published the photos in an article (5) that showed images of the bullet-ridden damaged buildings. It was then that Ismail Osman and Mohamud Dirios contacted me and told me that they had images of the same buildings when they were intact. This then led to the idea of the exhibition showing Mogadishu « then » and « now ».

The more I learnt about Mogadishu before the war, the more fascinated I became. I then embarked on research and interviewing people who had written about the city or who had once lived there. That then gave birth to the book.

Concretely, what was like for someone from outside the country, and for such a short duration, taking photographs in Mogadishu, a city that, as you point out on the back cover, « gained the reputation of being the most dangerous and violent city in the world »?

I think taking the photos was easier for me as a non-white woman. If I had been a white man or woman, it would have been more difficult as I would have stood out from the crowd. I felt the same years ago when I was photographing Kabul, just after the US-led coalition had liberated the city from the Taliban. As a woman it is easier to « fit in » and people are more accepting of you, even when you photograph them. This is especially so in conservative Muslim societies. I found it much easier to photograph women, for instance, as they did not perceive me as a threat.

I lived in a hotel in the centre of Mogadishu which had many Somali diaspora guests, so I got to experience the city like most Somalis do, without armed guards or « technicals » (6). The only time I felt a threat to my life was when a guard at a government building pointed a gun at me – I didn’t know that photographs of government buildings were prohibited.

While taking photographs in Mogadishu, were you specially attracted by buildings, architecture, and so on, or also by the interactions between people and the spaces around them (I’m thinking, for example, of the photograph of young people training in the stadium), by how people make the city their own, in spite of everything?

I could only operate within a safe radius, and did not go, for example, to Bakaarah market, which was still considered unsafe. I was with a Somali who lives in Nairobi, who served as my guide and told me about the buildings. I was particularly attracted to Hamarweyne, the old part of the city, where you can see the kinds of houses that are common on the Swahili coast of East Africa, including Mombasa, Lamu and Zanzibar. When I went to Stadio Conis, I did not expect to see runners training there as the place is bullet-ridden and worn down. But I noticed that the tracks were freshly marked, which meant that the stadium is being used despite its condition. I asked the female runners there if I could photograph them, and they didn’t seem to mind. There were also boys playing football, which seemed surreal as the stadium borders an IDP camp.

As you had never visited the city before, how did you handle your discovery of the city spaces? For example, did you prepare a list of places and sites that you had come to know through your readings?

Quite often, I could not get out of the car to take the photographs due to the insecurity. So many of the ones in the book were taken while the car was moving or stopped for a minute. I did, however, get out of the car in some places, such as Hamarweyne, where I had gone with the mayor’s wife and her security, so I felt safer. Generally though, I did not feel under threat. People didn’t seem to mind being photographed. One of the shopkeepers whose photo appears in the book specifically asked me to photograph her and posed for the photo. I did not prepare a list of places I wanted to photograph as I had no idea what was there. So I played it by ear, and photographed what I thought was worth capturing, and when an opportunity presented itself, I clicked.

During your stay in Mogadishu, did you meet local photographers?

Not really. However, on my second visit to Mogadishu in April this year, when I was invited by the mayor to launch the book, I met a lot of journalists.

About the historical photographs: you worked with Mohamud Dirios, who was a former curator for the Mogadishu Museums. What does the collection of the Somali Cultural & Research Center look like in terms of quantity and quality? How did you to select the old photographs?

Mohamud Dirios has been collecting photos of Mogadishu wherever they appear, including the Internet, for more than twenty years. Because so much of the original material was lost, damaged or looted during the war, it has been difficult to find original images, whether they be photographs, or postcards, or images published in books. Hence the quality of many of the images published in the book is not that great. But the point of the book was not to produce a high-quality pictorial book, but to showcase what exists. Dirios and Osman put together a collection, and I selected those I thought to be most appropriate for the book. Some could not be published because of copyright issues. However, many of the images were from postcards commissioned by the Siad Barre government, so are in a sense public property. Incidentally, I recently met Lino Marano, the Mogadishu-based Italian photographer, who had been commissioned by Barre to produce the postcards. He now lives in Kenya.

What was the book’s editorial trajectory? If I am not mistaken, the book was preceded by an exhibition that first took place in Nairobi and Turkey. What kind of interest did this initiative raise in each city?

While writing the book, I met the Turkish ambassador to Somalia, Dr. Kani Torun, who showed great enthusiasm for the project and convinced a Turkish company to sponsor the exhibition in Istanbul, where it was first shown at the Somalia Conference that Turkey convened in May 2012. The exhibition then came to Nairobi where it was shown at the Alliance Française for a whole three weeks in June 2012. I am told the Nairobi exhibition was a huge success, with people coming from as far as Garissa in north-eastern Kenya to view it. The opening in Nairobi was also a huge success with the Somali Prime Minister and other politicians from the Transitional Federal Government (7) making speeches. In April this year, we took the photos to Mogadishu, where they were shown during the book launch (8). Many of the young people who came to the launch had never known the city before the war, so for them it was revelation. Many commented that they didn’t realise that their city was once so beautiful.

Do you consider this work as finished, or do you think that there will be new developments in the future, maybe with the help of other people coming on board with you?

I am hoping to continue photographing and writing about Somali cities, and hope that in the future I can visit Kismayo and Merka, as I believe they form an integral part of the Indian Ocean culture that is unique to East Africa and the Horn. If I can find the money for further research, I would also like to look at the archives that exist on Mogadishu and other Somali cities in various parts of the world, including Italy, as I think there is much to learn and document about Mogadishu, which is little known to the general public. This book is just a first small step in documenting the history and culture of Mogadishu. Much work remains to be done, and I hope it will spur more research in this field.

1 – Rasna Warah is author of: Triple Heritage: A Journey to Self-Discovery (1998), Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits (2008), and Red Soil and Roasted Maize: Selected Essays and Articles on Contemporary Kenya (2011). Her website: www.rasnawarahbooks.com

2 – Our blog « Fotota » documented two other projects focusing on Somalia and photography as a vehiclefor memory and the future: « Vintage Somalia »[here] and « Discover Somalia » [here].

3 – Rasna Warah, « A Clash of Cultures », Mogadishu Then and Now, AuthorHouse, 2012, p. 32.

4 – Emblematic of this tendency, on August 11 2013, the Italian public television broadcast a documentary film entitled « Le ragazze di Mogadiscio vanno al mare » (« Mogadishu Girls Go to the Seaside » [here], which showed a certain effervescence, especially in the economic domain and in the real estate business, alongside the majors challenges and problems that the country has to overcome in the next few years.

Just some days later (14/08/13), the BBC informed that Médecins Sans Frontières was going to leave the country, after 22 years’ presence, following « extreme attacks on its staff »:[here].

Also of note, finally, is the recent running, on August, 31, in Mogadishu, of the second TEDx event (Technology, Entertainment, Design), a spin-off of the Californian « ideas worth spreading » TED [here], and three articles published in the international press on this topic: « Mogadishu TEDx Talk Challenged by Security Threats » (The New York Times, le 30/08/13 [here], « Somalia Celebrates that Ultimate Symbol of Recovery: the return of TEDx » (The Guardian, 30/08/13) [here] and « Mogadiscio l’espoir timide de la renaissance » (Le Monde, 4/09/13 [here]

As political scientist Alexandra M. Dias wrote: « Since the end of the transition in August 2012, international engagement and interest in Somalia’s new institutional architecture and leadership have been on an ascendant curve. However refuges flows and stays neighbouring countries reveal that conditions within Somalia remain uncertain. Security in Mogadishu has improved since 2013, but general conditions for Somalis are far from the minimum neede to survive on a daily basis without fear of threats to their lives or physical integrity. (« International Intervention and Engagement in Somalia (2006-2013): Yet Another External State Reconstruction Project? », in State and Societal Challenges in the Horn of Africa: Conflict and processes of state formation, reconfiguration and disintegration, Center of African Studies (CEA)/ISCTE-IUL, University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, 2013, p. 102. Free Access [here]

5 – The article « Mogadishu: Desolate But Still Standing » (The East African, 19-25 December 2012 [here] already offered large room to the question of memory (the memories of elderly inhabitants of the city and the youth’s visions of the future, who only know a permanent state of war. See, for instance, this passage: « As I passed a group of children sitting on a bullet-ridden porch, I wondered what it must be like to have known nothing but war all your life. How would these children adapt when – or if – the city returns to normal? What, if anything, would they miss about the city where they grow up? Which memories would they want to hold on to, and which ones would they want to forget? »).

6 – Armed pick-ups.

7 – Following the completion of the Transitional Federal Government mandate in August 2012 (to which Rasna Warah refers), the federal Parliament elected a new President in September 2012.

8 – After Istanbul in May 2012, Nairobi in June 2012, and Malindi in December 2012, the exhibition was held in April 2013 in a Mogadishu hotel. The book was launched at the Italian Cultural Institute in Nairobi in November 2012, and then in Mogadishu in April 2013.///Article N° : 11782