When, as a historiographic exercise, I was recently asked to ponder the history and meaning of « South African photography, » I realized that the whole question of the relation of locality to medium would first have to be reconsidered. (1) As a first response, in this short and speculative essay I suggest that in order to locate local significance in each instance of photographic reception and production, we may usefully look beyond the borders of photography to broader examples of images across media, between locations, and over time.

This approach is informed by my ongoing research on the visual culture of the apartheid period in South Africa, where I examine the ways that certain types of images were repeated, and recoded-their political implications altered-in different hands over several decades from the founding to the collapse of the apartheid state. (2) This approach is also in sympathy with other recent studies that seek to explore the intersection of what Deborah Poole has termed « visual economies, » instead of the history of a particular medium in isolation with a static interpretation across space and time. (3) Of relevance, too, is Hans Belting’s call for a general anthropology of the picture, where he considers pictures in three aspects for the purposes of analysis: in terms of image, medium, and body. (4) For Belting, a medium is a surrogate for the human body, a temporary material place holder for an image otherwise living in the mind. Following Belting, if we are speaking of photography isn’t it often the case that when we refer to « the medium » we in fact speak of the image on the surface of the paper or in the frame or on the screen? It is good to perceive the difference, especially if we seek cultural meanings by attending to the dispersal of images and their emplacement in various media in specific locations and specific times. My approach also follows that of photography scholars Elizabeth Edwards (in Raw Histories) and Geoffrey Batchen (in Forget Me Not) who have proposed that the meanings of photographs be sought through closer study of how they have been distributed, touched, retouched, and patinated-how histories of accretion can tell as much or more than a caption. (5) And it seeks to further my own earlier studies of what I have termed Africa’s « diasporas of images. » (6) Till Förster’s writing on intermediality is also a touchstone for this project. (7)

Images in photographs are set in place, they are held and beheld, they are handled and reviewed. These images are on the move: even if fixed in silver or in ink they become placed and embodied-in newspapers, museums, in minds, copied into and commented upon in other media. Images seen in photographs may have an afterlife in other media, in other histories, in other politics. They may also have a pre-history in other media, histories, and politics. In short, all images, photographic or otherwise, are potentially mobile, they inhabit bodies, and media, and minds. And at each instance of inhabitation a new nexus of histories and a politics of representation can be read.

When the visual economies model is proposed it is often as a means to destabilize naturalized concepts of geography and culture inherited from the colonial experience. It is also worth recalling John Tagg’s exhortation that « a photography » does not really exist as such, only many histories of photography each linked and defined by institutions, effects, interpretations, and uses which are not wholly tied to a singular medium. (8) But in studies that cite Tagg and Poole, despite the reference to wider circuits of exchange, the primary object of analysis often remains something loosely defined as photographic. I propose instead that we broaden the exchange model to allow a more inclusive consideration of images in other media, so as to understand more fully the intermingling of images and the historical experience of images precisely by attending to shifts in register that accompany shifts in medium. What follows may have wider applicability, but the tentative examples I set out are linked specifically to South Africa.

Much of what the world knows about South Africa is the result of the global dissemination of social documentary and photojournalistic photography. These have been mostly images of poverty, violence, and racial struggle conforming to a limited set of types determined by the desires of a metropolitan middle class. My own interest is to complicate the established narrative about South African life by showing other points of intersection with other realms of visual culture. I will point to some of those places of intersection where the photographic has not always been wholly adequate to the task of picturing, or has been dependent upon, has imitated, or has lagged behind other media in its attempt to document the experience of South African life-for instance in the expressive use of color, in the evasion of censorship, in attempts to control denotation, and in the marking and enactment of affect, agency, and subjectivity.

The standard narrative about South African photography could be summed up in a few words: colonialism, Drum, the struggle, and liberated art. (9) But we should say more.

Some scholars trace the history of photography in South Africa to at least the 1850s, when a number of studios in the Cape Colony began producing images of notables, public works, and picturesque views. (10) By the 1870s photographic specimen studies were also being made of the native population, in some cases using prisoners as models. (11) As elsewhere in Africa, late nineteenth century photography can only be fully understood in relation to, as Patricia Hayes states it, a « history of exploration, colonization, knowledge production, and captivity » linking progress in Europe to its effects in the rest of the world. (12) Photography was part of the European arsenal of technological advancements during the age of empire, and as such it served to both symbolize the power differential in the colonies and to bring the space of the other into visible order. (13)

The standard narrative skips quickly past this colonial period, to early apartheid in the 1950s and to the founding of the picture format magazine Drum. Drum was produced in Johannesburg and distributed throughout Africa. It followed the model of other international magazines like Picture Post and Life that included photographic essays as a central feature. But it differed in that its focus was the valorization of « urban black culture » in Africa, and it was the first publication in South Africa to feature a young generation of non-White photographers and writers. Its audience was mostly Black working class, and its outlook was consumerist, middle class, and cosmopolitan. Its images included pin up girls, stories of social life in the city, as well as investigative journalism about the brutality and absurdity of apartheid, and features on political heroes from the « independence decade » elsewhere in Africa. While it is not always mentioned of Drum photography, it is important to note that it was framed by advertisements: for cigarettes, tea, disinfectant, and skin lightening cream-that is, by the elementary commodities of the cosmopolitan African petit bourgeoisie.

From Drum, the standard narrative jumps again to the anti-apartheid battles of the 1980s, when « struggle photographers, » working in somber black and white, « embraced a social documentary mode that subordinated the image to the propagandistic needs of the moment » and individual style to the collective needs of the movement. (14) Then, in the 1990s, with apartheid over, it is claimed that photographers were « liberated » by the opening of markets for their work overseas, by the freedom to seek out more interior and aesthetic concerns, and to experiment with color. This story, says historian Jon Soske, has become sort of an art world cliché, and I agree. But I would also note how compelling it is to tell a neatly redemptive story about a people’s progress from oppression to self-consciousness, a narrative that I must admit I have followed in my own writing until now.

The problem is, it is not the whole story, and not even the whole story about photography. Considered in isolation, this dominant narrative about the history of photography in South Africa is not adequate in two respects. For viewers abroad it does not reflect the range of lived historical experience in South Africa. It also tells us little about how specific kinds of photographic images have been seen and understood in South Africa itself in relation to other aspects of visual culture.

The basic chronology is not in question, so much as what it leaves out: first, in relation to other expressive arts; and second regarding the vernacular uses of photographs themselves. What we need to figure out is where these two intersect with the better known history I just retold. I would like to point here to some brief examples that could lead to a more nuanced history. Each case merits further study.

Two common uses of photography in South Africa during much of the twentieth century were studio portraits and identity photographs. Though they have been researched in west Africa, these have less often been closely studied by scholars in South Africa where most emphasis has been on the exceptional history of social documentary and photojournalistic images from the apartheid period and on recent gallery art. (15) One of the most sensitive studies of old studio images was by a practicing photographer, Santu Mofokeng. Mofokeng’s project is also widely known, perhaps in part because it has been shown in the international art gallery circuit. (16) Called the Black Photo Album and created in the early 1990s, it took the form of an archival research project and then an installation art piece. Mofokeng went around Soweto asking families for old photographs, from the pre-midcentury period when an incipient black middle class was in the making, before apartheid had crushed the people’s hopes of future prosperity. He restored and copied the pictures, added what information he could find, and produced a slide show with the results. Mofokeng was saddened to learn that many of the remaining relatives saw these old pictures as foreign to their own experience and had locked them away. He concluded that the complex early history of race and class in black neighborhoods had been shut off to later residents after half a century of apartheid, and he determined to bring them back into living memory. What interested Mofokeng about these older studio images is how and why they were later hidden from view, as much as the actual visual information they contain or the fact that they were made in the first place. His re-exposure of them showed how a once-common practice had been forgotten.

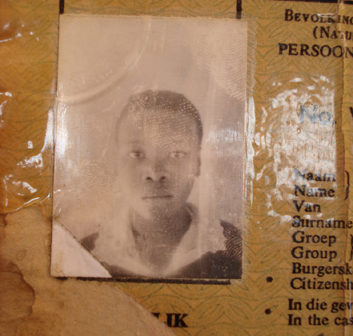

Among the most notorious policies in South Africa were the pass laws. From 1952 to 1986 every black South African carried an identity document, or dompas (slang for « dumb pass »), containing a photograph, fingerprints, and signatures of white employers stating that the bearer had a right to be in the city. These identity books were in a sense the most common form of photographic medium known to the vast majority of South Africans. They were carried everywhere, everyday, but what is their relation to the mainstream narrative about photography in South Africa?

One would think that these public images made by the state would be the antithesis of studio portraits made for willing sitters for private use. But there is also a tradition of photographic studios « enlarging and hand-coloring identity photographs of older relatives into family portraits. » (17) Similar practices are known from elsewhere, and they are discussed in Karen Strassler’s recent book on Java. (18) In the South African context, the thought that an image used to debase and control could be reanimated as a likeness for commemoration is intriguing. (19) A question animating my own current research is how to think through such positive re-uses of abhorrent images.

A related approach to memory may be seen in Rudzani Nemasetoni’s Litany series from 1999, where the artist has taken an uncle’s old passbook and retouched it with his own fingerprints, symbolically coming to terms with his family’s past by taking its images out of the hands of the state and holding them in his own. (20) A further commentary on the pass book is David Koloane’s Made in South Africa (1979), in which the artist, in an act of iconoclasm, destroyed his identity document but retained the picture, reframing and revalorizing it as a self-made work of abstract art.

Another example. It is commonly claimed, especially in relation to the evocative and well-known large scale portraits made by Zwelethu Mthethwa since the 1990s (of people living in informal settlements outside Cape Town), that through his vivid use of color photography the artist has at last introduced dignity and a positive record of black life-recalling that during the struggle only drab black and white images of the poor were seen. Such statements often look past the fact that color processing was not widely available at art schools or at newspapers in South Africa until the 1990s, and also neglect to mention the sensitive work in black and white (and also in color) by David Goldblatt, Omar Badsha, Chris Ledochowski and others dating from the heart of the struggle era. Commercial photographers working for glossy magazines, the artist Obie Oberholzer, and studio portraiture starting in the late 1960s such as the images made in Durban by Sukhdeo Bobson Mohanlall-these are other prominent exceptions to the common narrative of color development in South African photography. The example of color labs for family snapshots is another latent field for future research. Perhaps most egregiously, the color studies of Khayelitsha Interiors made by Ronnie Levitan in 1989, so strikingly similar to the later work by Mthethwa, have all but been erased from the history of South African photography. (21)

Art photography, it should be noted, did not, as the standard narrative tells it, begin after the first liberal elections of 1994, nor did it start any later in South Africa than it did elsewhere. There were pictorialists working in South Africa during the early 1900s and postmodernists in the 1980s. Considerations of artistic egos or which came first aside, the claim to precedence in the use of color is also untrue because even black and white studio portraits were often hand colored as well. Long before Mthethwa’s art had become a global commodity « the poor » had already taken the matter into their own hands and had (as they saw it) their dreary black and white pictures colorized. (22)

But the best place to look for a colorful, thoughtful, and positive record of black life from the pre-1990s era is to look not to photography alone, but also to the painters of urban scenes, beginning with Gerard Sekoto in the 1940s. The photographers may not have been able to shoot color in the 1940s, and the concern among them with documenting « the everyday forms of resistance to apartheid » may date to the 1980s, yet we can still look to the painters from earlier decades, like Sekoto, who brought everyday scenes of survival and an ambition for cosmopolitan success in the urban areas to life.

Use of color could also be critical, for instance in the acid-hued watercolors from Durant Sihlali’s Pimville series from the mid 1970s. The series documented the systematic destruction of older black neighborhoods by the Johannesburg city authorities, neighborhoods the artist knew from his early days as a child in a peri-urban settlement camp in the area that later became Soweto. In these works Sihlali styled himself as an old fashioned reporter, using watercolor to sketch instead of a camera to record, and he claimed the same evidentiary value for his images. Also, since he was not a photographer, it was less likely that his pictures would be censored by the State, even while he claimed that local residents sometimes chased him away in fear, accusing him of trying to steal their « shadow » when he painted them. I this respect he might as well have been a photographer.

Another comparison could be made by juxtaposing the black and white documentary realism of images by Eli Weinberg of Orlando township from the 1950s, which illustrated the harsh living conditions in the segregated black township by showing the imposing cooling towers of the Orlando power station looming over government-issued houses, with Sihlali’s rendition in watercolor of a similar scene. (23) In Slums, Zondi Township (1957), Sihlali painted the chimneys at a distance, rendering the scene instead as a lived-in landscape with a sort of desolate beauty.

While photographs of the more brutal forms of apartheid violence were censored, graphic artists had more indirect ways to express feelings about subjection and violence. Dumile Feni was much admired during the 1960s for his grotesque fantasy imagery, such as his Man with Lamb, a large work in charcoal from 1965. The animal and the human appear to switch roles in this image. And animal sacrifice is a screen for something else: the image is commenting on the threat of abduction and bodily harm by police and the sense of terror felt by the people after the massacre at Sharpeville in 1960. This is something that was widely experienced in 1960s South Africa, especially in the black communities, but it is something that could not easily displayed in photographs.

Or could it? In what must be the most famous image from the antiapartheid struggle, Sam Nzima, photographer for the black newspaper The World, depicted young Hector Pieterson dying in the arms of Mbuyisa Makhubu. Mbuyisa and Hector’s sister Antoinette are running from police who have just opened fire on protesting children on June 16, 1976. The image became a symbol of the struggle and it was broadcast around the world. Commentators have, I think rightly, spoken of how this picture had evocative power on an international level because it may be related visually to a whole history of pieta-type images in Christian iconography. I would add that this should remind us about how previous images from other familiar settings may often serve to activate meaning for an image from elsewhere. But also, recalling Dumile, this was a scene that in South Africa had already been imagined in advance. For Dumile it seemed bound to happen already in 1965. As it passed in front of Nzima’s camera, because it fit an already existing pattern, it became the right image. This was perhaps for different reasons at home, where Pietas but also animal sacrifice was known, than it was abroad. Clearly in this case, knowledge of the local history of image types is key to understanding the fuller local significance of Sam Nzima’s famous photograph.

The other five photographs taken by Nzima at the scene are rarely shown. One, of the child being placed in the back of the photographer’s car touches me personally because it shows something not often seen: the journalist caring for the injured subjects he has depicted. But it is hardly ever published. The newspaper The World was subsequently banned and Nzima fled to the rural areas. But in Soweto, the image from the paper on June 16 was burned into memory (perhaps because it was already there?)- as a sign of the sacrifices to be made for the coming revolution.

As an art historian/visual culture historian, I often find myself faced with these kinds of transformative moments, when the photographic image is dispersed as copies, including in other art media, and vice versa. In my own research I attempt to read the multiply embodied expressions of these complex images back into singular objects made in specific moments in history-and to read dispersion as the action of history. In a similar way, for students of photography it may be useful to think of how what is in front of the camera may also be behind it. Iconic images are always before the camera in this dual sense.

If universal histories are inevitably unstable ones, dependent upon other shifting histories of images at each new site of reception in each location and time, and we want to know what the expressive potential of the photographic is, then we also need to understand its cultural and historical definitions, that is, those places where the photographic touches other media and other histories. That is, if we seek a local history of the significance of photographs we need to be more attentive to the extra-photographic, to the other contingent image worlds. Because it is inevitably that which remains outside of the photograph, that determines its local identity. If there is such a thing as a South African photography, aside from the inadequate narrative that has been established for it so far, I am not sure yet what it would be, except perhaps a history of use based on a history of relations to other kinds of images in other media from other places.

1. Versions of this paper were presented at the Bonani Africa 2010 Festival of Photography, Cape Town, August 2010 (a conference on the state of documentary photography) and at the symposium The Developing Room – « Global Photography and its Histories, » Rutgers University, February 2011 (on globalizing historiography). My gratitude to Jon Soske, Omar Badsha, Andrés Zervigón, and Tanya Sheehan for the opportunity to begin rethinking how to interpret South African photography and for their comments during presentations. At Rutgers, contributions by Geoffrey Batchen and Karen Strassler were also helpful.

2. John Peffer, Art and the End of Apartheid (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

3. The original statement on « visual economy » approach, focused on the « production, circulation, consumption, and possession of images, » (8) may be found in Deborah Poole, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

4. Hans Belting, « Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconology, » Critical Inquiry 31, 2 (Winter 2005).

5. Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg, 2001); Geoffrey Batchen, Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (New York: Princeton, 2006).

6. John Peffer, « Notes on African Art, History, and Diasporas Within, » African Arts 38 (4) Winter 2005.

7. Till Förster, « Layers of Awareness: Intermediality and Practices of Visual Arts in Northern Cote d’Ivoire, » African Arts 38 (4) Winter 2005.

8. John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), 63.

9. This trajectory is almost universally restated, including in: Tosha Grantham, ed., Darkroom: Photography and New Media in South Africa since 1950 (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2009); Erin Haney, Photography and Africa (London: Reaktion, 2010); and Kathleen Grundlingh, « The Development of Photography in South Africa, » in Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, ed. Pascal Martin Saint Léon and N’Goné Fall (Paris: Editions revue Noire, 1999). Other studies have begun to give greater nuance to the standard narrative, see especially Patricia Hayes, « Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography, » Kronos 33 (2007); and Darren Newbury, Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa (Pretoria: UNISA Press, 2009).

10. The dating of inventions and first encounters is always contestable, as Geoffrey Batchen shows in Burning With Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997). Photography actually « arrived » in South Africa very early, since one of the inventors of photography, Sir John Herschel, sent a letter to friends in Cape Town in 1839 (the year of the announcement of photography in Paris) with a calotype (i.e. Fox Talbot’s paper process) affixed: a direct impression of a leaf. Another early « starting date » is 1846, when Jules Léger arrived via Mauritius and set up a daguerreotype portrait studio in Port Elizabeth. See Marjorie Bull and Joseph Denfield, Secure the Shadow: The Story of Cape Photography from its Beginnings to the End of 1870 (Cape Town: Terence McNally, 1970).

11. See Andrew Bank, Bushmen in a Victorian World (Cape Town: Double Storey, 2006).

12. Hayes, 141. In this passage Hayes also cites John Tagg’s idea that photography has no unified history.

13. See also the « Introduction » to Elizabeth Edwards, ed. Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992). And Peffer, Art and the End of Apartheid, Chapter 9: « Shadows: A Short History of Photography in South Africa. » The practice of making « native studies » was continued in later years, notably in the images made by Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin in the 1920s and by Constance Stuart Larrabee during the 1930s and 1940s. Its residue may be seen in later tourist-type images of the apartheid period and even in postcards for sale today.

14. The words are Jon Soske’s from, « In Defense of Social Documentary Photography, » in Omar Badsha, Mads Norgaard, and Jeeva Rajgopaul, eds., Bonani Africa 2010 (Cape Town: SAHO, 2010), 3. The author’s description is meant to isolate what he (and I agree) see as a false, or at least misleading or inadequate history.

15. There are notable exceptions, such as Andrew Bank and Keith Dietrich, eds., An Eloquent Picture Gallery: The South African Portrait Photographs of Gustav Theodor Fritsch, 1863-1865 (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2009). The pre-apartheid history of vernacular studio portraiture has been documented, though the practice continues into the present and this later period is less well studied.

16. Mofokeng’s images were most recently the subject of a retrospective at the Jeu De Paume in Paris in 2011.

17. Hayes, 143.

18. Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

19. Such re-portraits likely took the form similar to the framed image on the wall at top center in a photograph by Bob Gosani that ran in Drum in July 1956 (reproduced on page 247 of Grundlingh, « The Development »).

20. Reproduced in John Peffer and Lauri Firstenberg, eds. Translation/Seduction/Displacement (Portland: Maine College of Art, 2000).

21. For examples, see Ronnie Levitan, « Khayelitsha Interiors, » ADA 6, 1989.

22. This popular usage inspired Ledochowski to begin hand coloring his images of Cape Town residents during the 1980s. See Chris Ledochowski, Cape Flats Details: Life and Culture in the Townships of Cape Town (Pretoria: SAHO & UNISA Press, 2003).

23. Reproduced in Newbury, 224.///Article N° : 11101